LAYER TWO: PAPAL ROME

LAYER TWO: PAPAL ROME

The second layer of Rome looks into the Fascist regime’s contrary relationship with the Medieval, the Renaissance, and the Baroque periods of Italy, all lumped together under the strong influence of the Popes and the power of the Catholic church. After the fall of the Roman Empire, during the Renaissance, the Popes decided to rebuild Rome to its earlier glory, funding the city’s expansion. To leave a mark, these Popes, most prominently Sixtus V, raised dozens of obelisks, created monuments, and carved their names into the landscapes as testaments to Catholic imperialism and power in the church and state. Later, Italy came under the rule of various powers, notably the Spanish in Southern Italy, who funded numerous Baroque projects in Rome. When Mussolini began his rule in the 1920s, the marks of Papal Rome were a great consideration for him, on one hand representing a time where Italy was not “Italian enough” due to foreign influence, and on the other representing the imperial strength of the Catholic church and the rise of Rome to power once more, ideas that strongly appealed to the budding Fascist empire. The regime had difficulties deciding what to keep and what to demolish, what aligned with their policies and their tastes, and what was too different from the image they were carefully curating for themselves on the worldwide stage.

Site 1- Medieval Rome

This day centered around a general walking tour of many of the city’s important medieval sites and areas, focused from the 5th century to the 15th century. During this time period, Rome was changing, with a major loss of population and a shutdown of much of the city’s infrastructure. This allowed many people to move into a concentrated area known as the Campus Martius, repurposing ancient buildings into housing and public spaces, with spolia being used in much of the architecture. When the regime was demolishing areas and constructing their own Rome, they chose to keep the medieval-era architecture that embodied “romanità” and “italianità”, having elements that came directly from ancient times and were incorporated into the construction, whether it be style, material, or historical significance.

Santa Maria in Cosmedin. Photographed by Reid Graham.

Medieval-era housing and courtyard, still occupied by residents today. Photographed by Peter Ankerberg.

Casa dei Crescenzi. Photographed by Luke Lynch

Medieval housing, flanked by Ancient columns. Photographed by Erin Hobbs

Medieval housing. Photographed by Erin Hobbs.

Curved building, built on an Ancient amphitheater foundation. Photographed by Makenna Karst.

Site 2- The Road to St. Peter’s

St. Peter’s Basilica was a marvel of the Renaissance and Baroque periods, expanded during the Counter Reformation, with arching domes, enormous columns, detailed marbles, and gold being major components of the decoration. However, the road leading to it is a Fascist-era project, connecting the historical city center to the Catholic center of the world. The regime and the Church signed the Lateran Pact in 1929, reconciling church and state under the regime in terms of policy. The Via della Conciliazione, carved out by the regime starting in 1936 and completed in the 1950s, was a physical link between the regime, who had recently declared their Empire, and the Catholic Church, who are notorious for their imperialism throughout history. The road, lined with obelisks, which have been a symbol of conquest since ancient times, is a nod to the many obelisks raised by Popes throughout the time of Papal Rome. This road might seem to be a sign of the strong tie between the Church and the regime, however, the road itself is not perfectly aligned with the dome of St. Peter’s but rather the obelisk raised in the Square, signifying the regime’s alignment is to imperial power, not the Church.

St. Peter's Square and the Via della Conciliazione. Photographed by Erin Hobbs.

Obelisk streetlights on the Via della Conciliazione. Photographed by Reid Graham.

St. Peter's Square. Photographed by Luke Lynch.

Fascist buildings next to the St. Peter's colonnades. Photographed by Lucy Martin.

The domes of St. Peter's Basilica. Photographed by Peter Ankerberg.

Statues along the roof of St. Peter's. Photographed by Makenna Karst.

Site 3- The Renaissance Quarter

When the Popes decided to help rebuild Rome in the Renaissance after its loss of population and grandeur in the Medieval times, their areas concentrated in the area known as the “Renaissance Quarter” of the city. This area is filled with many churches that sprung up over the 1500s and 1600s when the Baroque style was being created in Rome. Several of these projects were funded by the Spanish, who held control over Southern Italy, but still had heavy sway even in Rome. Because of the foreign influence, the regime did not believe this area had the appropriate amount of “Italianness”, however, certain buildings that held enough Roman influence were spared due to their beauty and grandeur. There were some demolitions to better view the buildings, as well as a technique of diradamento, or “thinning” down building sides to create more picturesque views of these Baroque marvels, championed by Gustavo Giovanonni. Other areas were partially reconstructed by the regime such as Piazza Navona.

The Basilica of Sant'Andrea della Valle. Photographed by Luke Lynch.

Fascist-era buildings leading to the basilica of Sant'Andrea della Valle. Photographed by Reid Graham.

Building that once held fascist election propaganda. Photographed by Peter Ankerberg.

Obelisk of Piazza Navona, raised by Pope Innocent X. Photographed by Makenna Karst.

Fascist-era buildings framing the edges of Piazza Navona. Photographed by Lucy Martin.

Ancient ruins under a fascist-era building. Photographed by Audrey Huhn.

Site 4- Training Fascist Youth

The Foro Mussolini, now known as the Foro Italico, is a sports complex constructed by the regime to be a center for the training of Fascist youth, encouraging physical strength and the “ideal” form for a person. While the complex was designed by architects Luigi Moretti and Enrico Del Debbio and built in the 1930s, it draws on architectural forms that are both ancient and papal. With its black and white mosaics and its marble statues, the Foro uses favorite materials and decor from the Roman Empire in a way that furthers the regime’s ideology. The imposing obelisk and wide walkway lined with marbles that leads you into the Foro recalls St. Peter’s Square and the Via della Conciliazione, tying the complex to ideas of imperialism and Baroque-era urbanism. The site is notable for its incredibly high amount of Fascist propaganda and iconography that remain even today like mosaics, obelisks, and marbles celebrating the regime, even though the Foro continues to serve as a modern sports complex used for casual fitness and large events alike.

Mussolini's obelisk at the entryway of the Foro Italico. Photographed by Lucy Martin.

Marble procession of important dates of fascism. Photographed by Makenna Karst.

Field of Marbles. Photographed by Erin Hobbs.

Fountain at the Foro Italico. Photographed by Peter Ankerberg.

Fascist mosaics honoring Mussolini. Photographed by Luke Lynch.

Pools at the Foro Italico. Photographed by Peter Ankerberg.

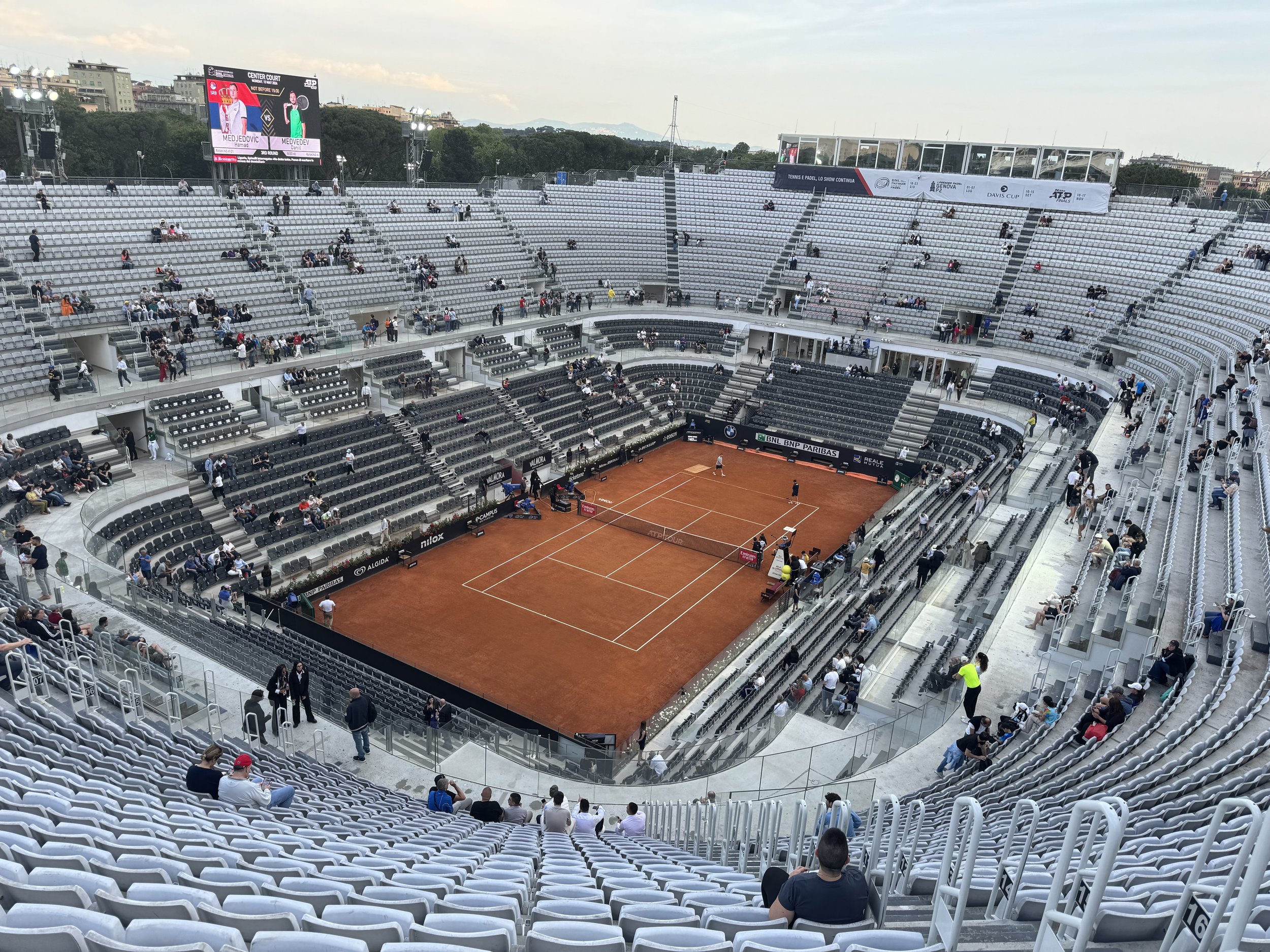

Italian Open tennis matches being held at the Foro Italico. Photographed by Makenna Karst.

Administrative buildings and training center of the Foro Italico. Photographed by Erin Hobbs.

Italian Open tennis matches being held at the Foro Italico. Photographed by Makenna Karst.

Site 5- Demolishing and Resurrecting the Baroque

The Church of Santa Rita da Cascia, originally designed by Carlo Fontana and constructed in the mid-17th century, was located at the base of the Capitoline Hill, next to the Scalinata dell'Ara Coeli. When the regime was creating the Via del Mare (now the Via del Teatri di Marcello), using mass demolitions to carve out space for the road, they discovered ancient and medieval ruins around the church. Because they believed these ruins to better represent the “romanità” they prioritized so much over the Baroque era church, they originally planned to demolish Santa Rita. However, architect and urbanist Gustavo Giovannoni loved the church and championed it as an example of the Roman Baroque movement. He fought for the building, and so it was carefully deconstructed and moved across the street, reconstructing it and situating it next to the Theater of Marcellus. Although careful documentation occurred, many parts of the church had to be fabricated, including the entire back wall, leading to many believing the church is no longer accurate to its original form, and instead has become an example of Fascist architecture rather than Baroque.

Reconstructed Santa Rita da Cascia. Photographed by Audrey Huhn.

Santa Rita da Cascia in its new location, with its old location in view. Photographed by Reid Graham.

Plaque detailing the Ancient and Medieval ruins excavated at the original location of Santa Rita da Cascia. Photographed by Lucy Martin.

The Vittorio and Scalinata dell'Ara Coeli. Photographed by Reid Graham.

Piazza del Campidoglio. Photographed by Peter Ankerberg.

Stumble Stones honoring those taken to concentration camps in the Holocaust. Photographed by Peter Ankerberg.